The Light from the TV Shows: Dean Stockwell discusses leaping into ‘NCIS: New Orleans”

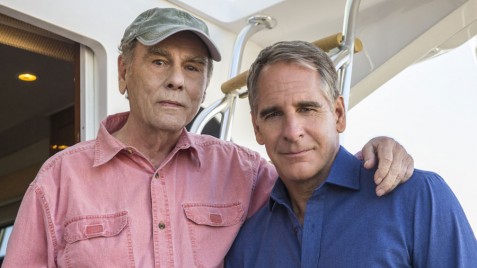

How did Dean Stockwell come to reunite with his former Quantum Leap co-star, Scott Bakula, on tonight’s episode of NCIS: New Orleans? The answer is about as simple as they come: “They called my agent and I was available, so I said I’d do it.”

This time around, though, Bakula and Stockwell aren’t playing partners…or even close: Stockwell’s character, Tom Hamilton, is a fella who’s suspected of having been involved in a murder 40 years earlier. Plus, if you’ve been watching the series at all, then you’ve already met Tom’s son: Councilman Douglas Hamilton, played by Steven Weber.

“It’s not a big part,” acknowledged Stockwell. “But it’s a key part, and it was great to be able to work with Scott, to go in and feel that comfortable with someone.”

Stockwell may not stay in regular contact with Bakula nowadays – it’s more of an “every once in awhile” situation – but “I’m very pleased for him and thrilled that he’s got this show. It’s always good working with Scott.”

And just for the record, the NCIS: New Orleans gig wasn’t just a favor for a friend: Stockwell’s always open to listening to an interesting job opportunity if one’s available. “If I get offers, I do them…but they don’t come all the time!” he said, laughing. “Now, I wouldn’t do a full-time series regular at this point, but a recurring role? Sure!”

Hey, you could do a lot worse than a guy who’s got 69 years of on-camera experience under his belt: Stockwell’s first film was the classic 1945 musical Anchors Aweigh, which found him starting his motion picture career at the ripe old age of nine years old, working alongside the likes of Fred Astaire and Frank Sinatra.

“I was unaware of how famous they were,” admitted Stockwell. “I just kind of melted into them and was unintimidated and had a good time. I thought it was kind of fun!”

Stockwell began his acting career as a result of his mother. “She was separated from my father – he was gone – and she heard about a play that was looking for children, so she took my older brother and I down to this audition,” he said. “We were both put in the play, and I had one line in the play: ‘I won’t be damned.’ That was my line…and if I’d forget it, as I did every once in awhile, my brother would say it.”

Looking back, Stockwell feels like one of the major turning points in his early career came with his performance in Elia Kazan’s Gentleman’s Agreement, released in 1947. When asked if Kazan taught him anything in particular, however, his answer is “no,” and he doesn’t look back on anyone else as having been a particular mentor when it came to acting, either.

“I just had my way of doing it,” said Stockwell, with an audible shrug. “And that’s the way I did it from the start.”

A few years ago, I had a longer and more in-depth conversation with Stockwell when he was in the midst of promoting his appearance in Battlestar Galactica: The Plan, and while it wasn’t on the level of, say, one of the Random Roles interviews I do over at the Onion A.V. Club, I still managed to bring up more than a few items on his filmography.

You can check out the conversation in full by clicking here, but I put together a list of highlights from the conversation…which, in fairness, is a pretty big chunk of the conversation, but so what? It’s Dean Stockwell. The man’s awesome. ‘Nuff said.

On playing John Cavil on Battlestar Galactica:

“He’s not a nice guy. I’ve played some very negative characters, and some of them were pretty good performances, and some of them were for, uh, stupid shows. But what made this so unique is that the character is a machine, right? So then I feel that, as an actor, I’ve got all kinds of freedom as far as how I want to play a machine. The thing that’s interesting about Cavil Two, who lives on Caprica, is that he develops a little bit…just a little bit…of a conscience. Or a little bit of sympathy – we’ll put it that way – for the humans. The idea that he’s a machine makes him unique, and then he goes ahead and…there’s a line of dialogue where Cavil One says to Cavil Two, ‘I have a yen to witness a nuclear holocaust.’ So it’s a yen for him. And he goes ahead and does it, and…you’re talking about billions and billions of people on all of these planets. He kills them all.”

On Neil Young and making Human Highway:

“I can’t remember first meeting (Neil Young), but I moved to Topanga Canyon in 1965, and then he got in there shortly thereafter, and there was just an amazing amount of wonderful creative activity in that canyon for several years. And I had written a screenplay that Dennis Hopper encouraged me write, and it never got produced, but somehow someone got a copy of it to Neil, and…he had been going through writer’s block for the better part of a year, and his record company was pissed off at him, and someone handed him this screenplay, he read it, and it just opened him up and inspired the album After the Gold Rush, which was the title of the screenplay. And even though I had Dennis behind me and I had Neil and all of this incredible music from that album, the fucking guys at Universal still wouldn’t make the movie. Pardon my French. But it’s just as well. Now, I look back over at a lot of years, and I don’t know if I was really ready to do a movie that, uh, people could follow. I think I would’ve stepped out a little too far.

“Human Highway was fabulous. That was great. I love Neil. I love him as much as anyone I love or have ever loved. He’s an absolutely great guy. Not only a super great artist, but also as a human being, he’s just beautiful. So we have a lot of fun, and so Human Highway was a lot of fun. The concept was Neil’s, and it had some silly-ass things to it, but I just went with that…and there you have it: Human Highway.I got (Devo) involved. I cast a lot of the people in it: Russ Tamblyn, Dennis, Devo, and several others. And not that it matters, but my favorite scene in the whole damned movie is Booji Boy in the crib singing, “Hey Hey My My.” (Laughs) That’s just fabulous.”

On Dennis Hopper (who was still alive when this interview took place in 2009):

“I met Dennis in Hollywood, around 1956 or ’57, and that’s a great, deep friendship there as well. Beyond what we’ve appeared in together, we’re the same age – I’m three months older than him – and we’re the same height, the same weight. He’s got different color eyes, but we’re both actors and we have been for a long time, and we’re both artists and we have been for a long time. I make art, too, and Dennis makes art…on a very, very heavy scale. I don’t know if you know it, but he’s the first living American artist to have an exhibition in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. Ever. He makes these big canvases, and there are also photographs, but he had 12 canvasses, and right after the start, he sold eight of them. And out of 140 photographs, he sold 100. He’s one of the hottest artists in the world, forget about him as an actor. Seriously, in the world.

On Gentleman’s Agreement:

“I was aware that Gentleman’s Agreement was a controversial thing. I was aware from the content of the scenes that there was something wrong in the world when people had prejudices against one race or another. So, yes, I was aware of it, and I took it seriously, just as I took The Boy with Green Hair seriously: because it had a meaning. It was an anti-war film.”

On Werewolf of Washington:

“That was a real heartbreaker, because the screenplay was really funny. Really funny. And the fellow that directed it, Milton Moses Ginsberg, he had made one film prior to that, which was called Coming Apart. It was all about a psychiatrist looking through a two-way mirror at his patients. Was it Rip Torn…? Anyway, that film did well, because the guy had a lot of wonderful ideas, but none of them…none of them…had to do with the camera. Because the whole film was shot with a locked-off camera. Okay, so here we go, we’re going to start this Werewolf of Washington, which, like I said, had a wonderful script. But the guy doesn’t know camera right or left! He just doesn’t know it, and he can’t figure it out. Even the D.P. tried to help him, but he couldn’t do it. So it became impossible to edit the thing! It was really a heartbreaker, because I had great high hopes for it, and I think I have some pretty funny scenes in it.”

On working with David Lynch and Wim Wenders:

“I think they have an artistic vision, and I think that both of them have much more of a capacity to improvise and create on the spot than other well-established directors. And…well, say, in the case of…is it David? One of them – I can’t remember which one! – doesn’t like to know how the film’s going to end until he’s well into it, and you wouldn’t find any major studio director starting into a film without knowing how it’s going to end. I always thought that was kind of funny. But I love both of them, and if they came and asked me to come to Asia and film a screenplay for nothing, I’d do it. They’re really great guys.”

On Psych-Out:

“I haven’t seen (Psych-Out) since it was released. It was just a money job. Even at the time. I’ve got categories of jobs, and one of the categories is ‘money jobs.’ If one of those comes along and I have to make a living, even if I don’t like the script that much, I’ll do it and just try to stay above water, which I’m able to do most of the time. I try not to sink with the ship.”

On The Boy with Green Hair

“If I had to pick a favorite, it’d be The Boy with Green Hair. That’s got such an underlying meaning to it. And the main players on that film…the director and two of the producers were blacklisted by the Hollywood Blacklisting. The director, Joseph Losey, never made another film in the United States. He said, ‘Fuck you,’ and he left. He went to England and made his career there. Because they thought this was an anti-war movie, which of course means that they were Communists. Totally crazy. Totally crazy. And I wouldn’t be surprised if I was still on a list somewhere.”

Related Posts

Comments Off on The Light from the TV Shows: Dean Stockwell discusses leaping into ‘NCIS: New Orleans”

Posted in: Uncategorized

Tags: Anchors Away, Battlestar Galactica, Battlestar Galactica: The Plan, David Lynch, Dean Stockwell, Dennis Hopper, Elia Kazan, Frank Sinatra, Fred Astaire, Gentleman's Agreement, Human Highway, NCIS: New Orleans, Neil Young, Psych-Out, Scott Bakula, The Boy with Green Hair, The Light from the TV Shows, Werewolf of Washington, Will Harris, Wim Wenders