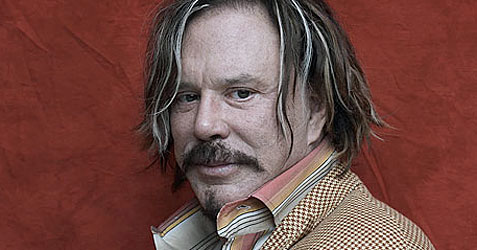

A chat with Mickey Rourke (“Immortals”)

“9 1/2 Weeks” director Adrian Lyne is supposed to have said that if Mickey Rourke had died in 1986, his legend might have surpassed James Dean’s. Maybe so. The problem was that, after a series of usually superb but always entertaining performances, Rourke didn’t die. Instead, as the man himself explains, artistic hubris and psychological issues got the better of him. He developed easily the worst reputation of any actor in Hollywood before quitting show business for a time to become a boxer at age 39. Though the resulting injuries and reconstructive surgery permanently altered Rourke’s appearance, years of public fence mending and consistently strong work in small but memorable roles have finally paid off. The battle-scarred actor is now enjoying the afterglow of a sympathetic, engaging, and just plain damn brilliant Oscar nominated performance in Darren Aronofsky’s 2008 indie hit, “The Wrestler.”

A former amateur boxer from Schenectady, New York, Rourke first got short-listed for the A-list with his charismatic turn in Barry Levinson’s 1982 ensemble classic about masculine immaturity, “Diner.” That was followed by a series of highly notable films that didn’t impress at the box office but live on in home video: “The Pope of Greenwich Village,” Francis Ford Coppola‘s tragically underrated “Rumblefish,” Michael Cimino’s “Year of the Dragon,” Alan Parker’s “Angel Heart,” and Barbet Schroeder’s charming 1987 Charles Bukowski adaptation, “Barfly.” Prior to “The Wrestler,” Rourke was probably best known for 2005’s “Sin City” and 1987’s “9 1/2 Weeks,” which also did a lot to popularize co-star Kim Basinger and the erotic use of ice cubes.

I spoke to Rourke via phone about 24 hours prior to the press junket for “Immortals,” Relativity Media’s hyper-violent mythological fantasy film directed by visual stylist Tarsem Singh (“The Cell,” “The Fall”). When I cheerfully asked the star how he was, his response was a weary, “Oh, that depends.” What else should I have expected from one of acting’s most respected loose cannons?

Bullz-Eye: It’s an honor to talk to you.

Mickey Rourke: Thank you.

BE: We’ll start with “Immortals.” I think this might be your first real period film.

MR: Yeah, close.

BE: And also it’s your first 3-D film. A lot of green screen; a lot of effects. How did that affect your approach?

MR: It doesn’t really. I mean, I got used to the green screen two years back when I did “Sin City” with Robert Rodriguez.

BE (embarrassed I forgot about it): Of course.

MR: You know, everybody says, “Oh, it’s a green screen,” but it’s just another aspect of making movies. It doesn’t really get in the way with me.

BE: And the 3-D, you don’t even think about it?

MR: No, you don’t even know. I mean, I don’t deal with that stuff. Shoot it in 6-D, I don’t give a fuck.

BE: Okay, now you’ve played a lot of anti-heroes and questionable type people, but you’ve never really played a whole lot of nasty villains like Hyperion in “Immortals.”

MR: Yeah.

BE: And here, you’re not only a bad guy but you’re a king. You’re an authority figure.

MR: Right.

BE: I know you’ve been very frank in interviews that that’s an issue for you. I wonder if you maybe imagined he was your least favorite producer or studio head.

MR: Oh, my least favorite producer was Elliot Kastner. He’s dead.

BE: But I mean, when you were playing him, were you thinking of somebody in particular?

MR: Oh, the king you mean?

BE: Yeah.

MR: Not necessarily. My whole thing all the time is, let’s not make a one-dimensional bad guy. Let’s give him some layers and justify why he is the way he is.

BE: Sure.

MR: There’s always a fight.

BE: So you’re trying to maybe even give him some good qualities.

MR: Absolutely.

BE: You’ve worked with a lot of visionary directors in your day. How about Tarsem Singh? What’s he like compared to people like Coppola, Cimino and Aronofsky?

MR: He’s just very prepared and he knows exactly what he wants to do. Like I said in the last interview, the wardrobe lady, [Eiko] Ishioka, was working on the film for a couple of years before we even made it. [Tarsem] had done a very extensive pre-production and a lot of research, too, on that particular period of mythology or whatever. He just knew what he wanted. That makes it all really easy for me. I just have to put on my tights.

BE: I was watching your 2008 Charlie Rose interview last night, and you mentioned that you liked directors that kind of push you a little bit.

MR: Yeah, well Tarsem doesn’t really push you that way. He’s just intellectually prepared.

BE: Right.

MR: He gives you interesting activities. Or he’ll even say, “Don’t even say all those lines, just do this,” you know? He’s very spontaneous and he’s not so concerned with the dialogue as he is with creating the moment. So he’s very much open to an almost improvisational type delivery, with structure.

BE: He’s flexible.

MR: He’s flexible in a smart way because, like I said, he knows what he wants. When somebody knows what they want, you get a lot more, I think, out of the actor and the message that comes across.

BE: Gotcha. Moving on to “The Wrestler,” and of course I’m sure you’ve heard a few times that you did pretty good in that movie. I’ve noticed that a lot of really good actors, more than I would think, have a pretty serious athletic background, like you certainly do. What do you think the connection is between athletics and acting, if there is one?

MR: Oh, with me it was I just wasn’t good at any one particular sport to continue my career on. I’ve always much more enjoyed athletics than making movies. I think it’s a good nucleus and a good base, because it’s all about dedication and hard work. You just keep on trying to persevere and make yourself better, you know? And when you fall down, you have an instinct and an understanding to get back up. It is all about winning, but it’s also about if you make a gigantic effort and even if you lose, then you can be proud of the effort that you made.

BE: Right.

MR: You know, I can relate really good directing to a really good coach or a trainer.

BE: Now as far as working with actors, do you have a favorite of the directors you’ve worked with?

MR: Probably Cimino, Coppola, Adrian Lyne. Liliana Cavani [Rourke’s director in the 1994 drama, “Francesco,” in which he played St. Francis of Assisi, which means that “Immortals” is not his first period film]. Aronofsky, of course, even though he’s a hard motherfucker. But I would go to work for him again, you know. I would work with Tarsem again because he’s a really smart man. Well, first of all, Aronofsky and Tarsem are really bright guys. They’ve got really large brains and they help make my job easier because if I make a choice, they sometimes give me an adjustment and say something that will be a better choice than I made. That’s what makes the acting interesting. I don’t know if I would have done this particular material if it wasn’t [for] Tarsem.

BE: You wanted to be with somebody kind of on the interesting side of things.

MR: Well, even if [the movie is] seen as mediocre or ordinary, he’s such a visionary and he’s so bright he can transcend the material.

BE: With you, there’s kind of an obsession out there with your very dramatic career. Again, listening to the Rose interview last night, I was thinking that the moment that I started to think that you were eventually going to come back was probably before you think it was, which is “The Rainmaker” (1997).

MR: Well, you know, it’s funny. I think what happened with that was once again Coppola gave me a shot to do that when I couldn’t get any work in Hollywood. And it didn’t really happen after that. My reputation at that time was still so bad that they didn’t care how good I was in that movie. You know what I mean?

BE: It took more than one movie.

MR: They weren’t going to let me back in the door yet. At that period of time there were still too many people around that I had pissed off. I had to wait another several years for them fuckers to die off.

BE: Okay. This is a question that I like to ask people who have done a lot of movies. Of all the movies you have done, which one do you think didn’t get the attention it deserved?

MR: I don’t know. My favorite movie that I ever did up until now is “The Pope of Greenwich Village.”

BE: It’s funny you mention that. Believe it or not, that was maybe the one major film in your filmography that I had not seen and I just caught up with it the other night.

MR: Yeah.

BE: That is the darnedest movie.

MR: The studios had changed studio heads at the time so it was a new regime that came in and nobody really wanted to push the movie. It probably was the most fun I’ve ever had on film. And Eric Roberts is definitely one of the best actors I’ve ever worked with.

BE: You two have a really fascinating dynamic in that movie. The one that I’m a big fan of, and the one where I saw you and went “Oh my God, this guy is a movie star,” was “Rumblefish.”

MR: Well, that was sort of an early introduction to working in a very unconventional way. Once again, you take Rodriguez and Coppola and Tarsem, and they are all sort of the same kind of big brain visionary person that doesn’t work in, let’s say, your A-B-C kind of way.

BE: Right. “Rumblefish” was remarkable at the time. You didn’t know what time period it was set in. It could have been the 50s, it could have been the 80s. You didn’t know.

MR: The studio at the time wasn’t so hot about it. But I know when it went to France, all of the French loved it.

BE: The French, and me and everyone at UCLA where I was. Now you got a lot of attention in the old days for passing movies up. Were there any that you were particularly happy that you passed up?

MR: Sure, I can’t mention them though.

BE: Oh, darn it.

MR: You know, I’ve learned my lesson about pissing those people off so I’m not going to name the names. But yeah, there’s quite a few movies that I regret passing up for stupid reasons back in the day. And sure, there’s a whole bunch that I’m glad that I didn’t do.

BE: Are there any directors right now that you’re really anxious to work with soon?

MR: I’d like to work with Adrian Lyne again and I’m always open to working with Francis.

BE: I know you’ve had close calls with Quentin Tarantino a couple of times.

MR: But he talks a lot.

BE: Yes, he does.

MR: What can I say? You’ve got to be able to decide who you’re going to talk to and how you’re going to say it.

BE: Right… you see in the press how they tend to leak these stories about how so and so is thinking about being in a movie and so and so is circling something.

MR: Well, you know, I don’t know how to say it politely.

BE: Well, what have you got coming? I was looking on IMDb and there are some interesting sounding movies coming up.

MR: I’m mainly going to take some time off now and get ready to do my rugby movie that I wrote. It’s about a rugby player who’s gay. His name is Gareth Thomas and I wrote a script called “The Beautiful Game,” so I’m doing that next.

BE: Cool. And this is not the first script that you’ve written. There was a movie you did with Tupac several years ago called “Bullet.”

MR: Yeah, there are about four that I’ve written.

BE: So now, you’re going to be in it?

MR: Yeah.

BE: I don’t know about the story, Are you playing him or are you playing somebody else?

MR: You can Google him, it’s Gareth Thomas, he plays for Wales.

BE: Okay. And who’s directing?

MR: A South African director named Antony Hoffman.

BE: Sounds really interesting. How do you think you’re acting background works when you’re writing?

MR: It’s more life background. Well, yeah. It’s so important to write the other characters as good as you write your character. So, coming from the acting background, there’s certain actors that I have in my mind that I want to use in certain roles. If I’m writing something and it’s for this particular person, I have the responsibility to write his role as good as I would write my own role.

BE: Sure.

MR: So I have to write all the main roles, or even if it’s a one-line guy, with some layers and with honorable intentions, in a way.

BE: Do you find yourself kind of having fun maybe trying to get into the head of somebody who in a role you would never ever be cast in?

MR: Say that again.

BE: In other words, you’re writing the part of a character that you know you would never be cast in. Just physically, you’re wrong; it’s a woman, say. Do you find as an actor you can get into your head a little bit maybe and get into her head?

MR: Yeah, sort of, you could do that.

BE: Okay, moving back into your filmography, I have a weird question. I have no evidence to support this, but with Barry Levinson’s movie after “Diner,” “Tin Men,” it always seemed to me [something was going on] because, at the end of the movie, your character gets a job [selling aluminum siding] with a character played by Michael Tucker…

MR: In which movie?

BE: We’re going way back to “Diner.”

MR: Oh “Diner,” yeah.

BE: Yeah, and your character, he gets a job [selling aluminum siding] working for a fellow named Bagel, who was played by Michael Tucker [who reprised the role in “Tin Men.]

MR: Right.

BE: It just seemed to me that the character played [in “Tin Men”] by Richard Dreyfuss was kind of like your character. I always wondered if maybe at some point that was intended to be more of a direct sequel.

MR: You know, I didn’t see that movie so I don’t know.

BE: So you never heard anything about it.

MR: Yeah. You obviously know your film history.

BE: I’m a fan. So, let me ask you this, when you go to see movies, what do you like to see?

MR: I don’t go to movies.

BE: Really?

MR: Yeah. I mean, I watch on the DVD and Apple TV. I just cruise through independent movies usually, the foreign films.

BE: Right. Well, let me ask you this, as a writer, who would you say your big influences are?

MR: Probably Pinter and Tennessee Williams combined.

BE: I was looking at a quote from when you were doing “Barfly” and you mentioned you were impressed by working with Charles Bukowski a little bit, but it wasn’t like he was Tennessee Williams.

MR: Not that much.

BE: Well, right, that’s what I was saying, it wasn’t as if he was Tennessee Williams to you.

MR: No, his wife was a jerk.

Perhaps not surprisingly, right at that moment the publicist decided to move things along, but that wasn’t quite Bullz-Eye’s last encounter with Mickey Rourke. I met again with Mr. Rourke not long afterward. This time it was in person but also in the company of a table full of my fellow entertainment journos at the L.A. Four Seasons. Provided with an audience and allowed to have a smoke outside for a moment, Rourke was in a carefree mood, asking inquisitors about where they were from and, at one point, administering playful noogies to a female writer who, fortunately, took it all very much in stride. Below are a few highlights, starting with another question from yours truly.

BE: Now that you’ve done…

MR: Where are you from?

BE: Los Angeles, actually.

MR: Oh, you’re the one.

BE: Yes. Anyhow, now that you’ve done a sort of classical period role, are there any famous classical roles you’d like to do from mythology or Shakespeare, say.

MR: [When I was a kid] I’d have trouble sleeping and my grandma would read me all that stuff. I like that. It’s very soothing and relaxing to hear all about those crazy things that you hope are real. I don’t have any plans though. First of all, directors like Tarsem don’t fall out of trees, so I don’t know what he’s gonna do next. If Tarsem was going to do another piece different than this, I’d work with him again. I know Darren Aronofsky is gonna do Noah’s Ark. If there’s a small part in that to work with Darren, I would gladly work with Darren — if he pays me this time.

Journalist: Do you agree with the assessment [in the “Immortals” press materials] that your character was like a Greek mythology version of Charlie Manson?

MR: No, not at all. I don’t know who came up with that…That’s terrible, that’s them trying to make [Hyperion] a one-dimensional evil bastard. This is what I fight with them pricks about.

Journalist: How would you describe him?

MR: He’s a guy who’s got some territorial issues, you know? It’s his block, okay? He owns everything in the neighborhood. What’s wrong with that? He earned it and this sissy wants to come over and start shit, I gotta cut his head off.

Journalist: You have a great fight scene at the end with Henry Cavill. What’s your view of him? He’s going to be Superman [in Zack Snyder’s upcoming reboot] and he’ll have this Hollywood machine come at him.

MR: I liked him because Henry was so enthusiastic, doing his push-ups and all ready to go to work. It was easy. He was nice. I don’t particularly care for actors myself and he is at a place right now where he is still a good person. Doesn’t behave like an actor, you know what I mean?

Journalist: When you turn on the TV and you see “9 1/2 Weeks,” do you turn it off? Do you like watching yourself?

MR: I never watched that movie until about five years ago…I saw it [again] about a year or so ago, like little pieces of it and I said, “That fuckin’ Kim [Basinger] was hot as shit!” I used to go home with a boner every night. Really. That was no fun…

Journalist: When you’re flipping through the channels and see yourself in something from a long time ago, does that take the form of a sort of out-of-body experience.

MR: No, it’s depressing. I’m going, “Oh, I’ve got so fucking old. I used to be much better looking.” Now it’s terrible. It really sucks, to see yourself deteriorate. I don’t know how [actors] do it.

Related Posts

You can follow us on Twitter and Facebook for content updates. Also, sign up for our email list for weekly updates and check us out on Google+ as well.

Posted in: Entertainment, Interviews, Movies

Tags: 9 1/2 Weeks, Adrian Lyne, Darren Aronofsky, Francis Ford Coppola, Immortals, Mickey Rourke, Mickey Rourke interview, Tarsem Singh