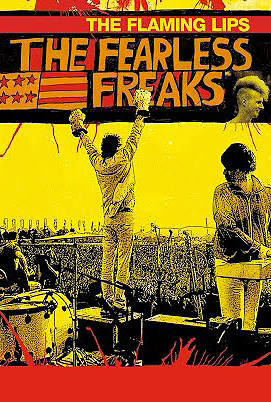

Missing Reels: “The Fearless Freaks” (2005)

Missing Reels examines overlooked, unappreciated or unfairly maligned movies. Sometimes these films haven’t been seen by anyone, and sometimes they’ve been seen by everyone… who loathed them. Sometimes they’ve simply been forgotten. But in any case, Missing Reels argues that they deserve to be seen and admired by more people.

“You don’t even have to be a fan of the music!” That’s a lie that people often spread about music-centered films. Whether it’s a biopic, a documentary or a concert film, fans of the movie will insist that, in order to like it, viewers don’t even have to like that particular artist’s music. It simply isn’t true. If you don’t like Ray Charles music, then those recording sessions in “Ray” will seem fruitless; if you’re not a fan of The Talking Heads, then “Stop Making Sense” is an interminable bore. No matter how well crafted the film is around those scenes, or how well shot the performances are, if you don’t dig the music on display, you won’t really like what’s happening on screen.

So I won’t repeat that lie here about the music of The Flaming Lips when watching the documentary “The Fearless Freaks.” I will, however, say that there’s a lot more going on here than just the music, which is true of the band itself. The Flaming Lips have always been about the experience, whether it’s their four-disc Zaireeka album played simultaneously, or their freak-out concerts, and the same goes for the documentary which covers their odyssey from crappy punk band to psychedelic musical masters. It helps if you’re already partial to some of their music to enjoy this film, but if not, then hopefully you can enjoy its simple story and arresting images.

While its 30-year history has seen a revolving door of members come and go, director Bradley Beesley chronicles the Lips’ humble origins by focusing on one of the mainstays throughout all of its incarnations: frontman Wayne Coyne. Coyne started off as just the guitarist for the band, while his brother handled vocals, but eventually Wayne took center stage, becoming the driving force in many ways. And so Beesley looks at his working class beginnings, the fifth of six children, and how the band grew out of that motley crew of children who were more interested in drugs, being artists and being different than being good at instruments. A true punk ethos of “anyone can start a band” pulsates throughout the Lips’ early days as they careen ahead with their lack of talent but intent on being the loudest and most memorable live band. This adherence to audial intensity and performance art would carry through the entirety of the band’s life.

One thing that makes “The Fearless Freaks” works so well is how Beesley, despite being close to the band (and Wayne Coyne in particular), is able to get enough distance that he can see through lines in all of the lives and careers involved in The Flaming Lips. The title of the documentary comes from the sandlot-esque pickup football league that the Coynes organized in their youth. It was a mix of druggies, artists, dropouts and rebels, literally colliding against each other in a spectacle on the field; there was blood and pain, but everyone had a good time. That same collision lives on in the Lips’ music and stage shows, with many influences coming together to produce something sonically interesting, philosophically probing and visually arresting. From the impoverished streets of Oklahoma City, to the giant concert halls of Hollywood, Beesley is able to connect the dots and show these recurring themes of scrappy DIY attitude meeting disparate influences produced a celebrated musical act.

Another aspect of the film that’s so well done is Beesley’s indulgence in multiple weird tangents throughout the movie. He examines the neighborhood that Wayne lives in, which is right near where he grew up, along with his relationships with his various siblings (and their various drug and legal troubles). Beesley takes time to explore the bizarre “Christmas on Mars” film that took about eight years to make (at the time of the documentary, it was still a work in progress), showing it as an example of the off-center way that Wayne Coyne filters the world through his senses and an extension of the band’s approach to creation. He revisits old stomping grounds with bassist (and other surviving original Lips member) Michael Ivins, and speaks with his supportive parents about their “should’ve been a professor but was a punk rocker” son. Viewers see Wayne Coyne covered in blood on stage one moment, and then watch as he has to scrub that blood clean from his suit (as well as the origins of the blood soaked suit). These tangents give the film room to breathe and help inform the offbeat nature of the band without adhering to just an infomercial about them. It’s an oral history with lots of digressions, and each one pays off with some emotional punch or insight into a unique process.

These tangents also pay off in the other heart of the film (Can a film have two hearts? Why not? It makes sense for a Flaming Lips picture to be anatomically grotesque): Steven Drozd. Drozd joined the Lips in 1991 as a drummer, but his musicianship is almost unparalleled. Even those who aren’t fans of the music The Flaming Lips make will be impressed by Drozd’s musical abilities. He can play any instrument, incredibly well, and seems able to conquer any new technology that comes out to help him complete his sonic goals. People probably want to make parallels to other musical partnerships in the past – Lennon/McCartney, Page/Plant, Townsend/Daltry – but there really isn’t an analogous duo: it’s clear that Drozd is the musical driving force in the band, while Wayne Coyne is the showman who takes his bizarre lyrics and makes them living experiences. This symbiotic relationship is evident throughout the film, even before the moment Drozd “joins the band,” as Beesley checks in with the Drozd family and starts building up the musician’s story. It’s clear that The Flaming Lips and Steven Drozd were fated to collide, like amped up teens on a football field, and that they would do something great together.

Beesley also handles the requisite darker matters very well, as are inherent in any long history of a people. Whether it’s restaging (to pretty hilarious effect) the time Coyne almost died in a robbery while working at Long John Silver’s, or having the surviving Drozd family members (the mother died and two siblings died by suicide) jam out together for the first time since Steven’s brother was released from jail, or even having Coyne reminisce about how his dad’s death really shook him in ways that would haunt his music for years to come. They are all done in a brutally honest yet tender and relatable way. These stories and circumstances aren’t unusual to encounter in the world (they aren’t even enough to fill out a particularly juicy episode of VH1’s “Behind the Music”), but the fact they are so mundane is what makes them relatable and what makes the music open up and make a lot more sense. And then there’s this scene:

Possibly the best anti-drug PSA since “Requiem for a Dream,” Drozd openly using heroin and discussing his addiction in a chatty manner is eerie and disquieting in a way that’s hard to narrow. He’s probably just amped from having scored his latest hit, but the enthusiasm mixed with the brutal honesty about how he’s sorely fucked over his own life is an incredibly powerful moment. Beesley is objective in his filming style, but his editing lends a subjectivity and humanity to the proceedings that easily draws in viewers and has them relate while being astonished.

The Flaming Lips has never just been a band. Even those who hate them, or point out (as this film does) that they are derivative of other groups like Butthole Surfers, have to concede that they have done things differently to make sure they’d be seen as an experience. An experience is something that happens to you, something that marks you, something you remember and relate to others – good or bad – and something that stays with you. By chronicling the band in this mixture of objective historian, friend and curious onlooker, Beesley is able to produce a signature documentary that delves into the psyches of three men and the long, strange journey they’ve been on. It helps to like the music of The Flaming Lips to appreciate “The Fearless Freaks,” but there’s certainly enough interesting material that it’s not totally dependent on it.

Related Posts

Comments Off on Missing Reels: “The Fearless Freaks” (2005)

Posted in: Entertainment, Movies

Tags: Missing Reels, Staff Picks - Movies, The Fearless Freaks, The Flaming Lips