The Buddy System: How Shane Black has continually reinvigorated and redefined the buddy cop film

While usually thought of as a hackneyed cliché from the ’70s and ’80s, the buddy cop film has actually been around a lot longer than that. Some trace its roots back to Kurosawa’s 1949 film “Stray Dog,” with early adopters being the politically charged “In The Heat of the Night” (1967) and the “I Spy” TV show in 1965. But it really grew legs with such films as “Hickey & Boggs” (1972), “Freebie and the Bean” (1974) and “48 Hrs.” (1982), each adding to the genre its own flair and nuance. (Please note: while the term is “buddy cop,” in this post the genre includes films with people that aren’t necessarily police officers; rather it’s just two, usually mismatched, partners joined together to solve a mystery.) So although it’s not as if famed filmmaker Shane Black invented the buddy cop film, for the past four decades, he has reinvented and reinvigorated an otherwise predictable and tired genre by using recurring tropes, witty banter and impressive action.

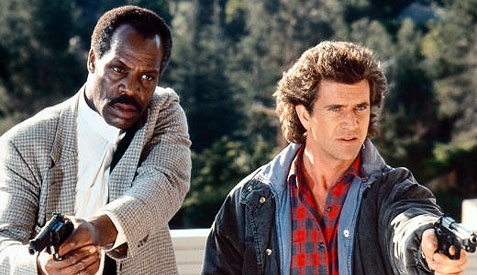

After “Die Hard,” “Lethal Weapon” is easily the most influential action film of the last 35 years. The spawn of homages and knockoffs that came after it is staggering, using Black’s template of the loose cannon and his straight-laced partner who engage in comic repartee while also delivering explosive violence. But many of the imitators that followed, including the “Lethal Weapon” films where Black isn’t involved (although he originally scripted the 1989 follow-up, it was heavily rewritten), missed that special mystery ingredient he brought to the first entry. “Lethal Weapon” is unique not just for its go-for-broke take on action, but also because it begins the type of story and archetypal characters that Black would revisit time and again over his career.

Roger Murtaugh (Donald Glover) is the straight-laced, conservative family man cop who just wants to retire in peace; Martin Riggs (Mel Gibson) is the wild child, ex-special forces guy with a penchant for violence and a few serious traumas in his past. They are a couple of outsiders, usually marginalized by society (a black man, both Vietnam veterans), who band together to take on an older man who represents exploitation of the military-industrial complex. While Riggs is incredibly competent and shines in his moments of heroism, Murtaugh also has an opportunity to prove himself and takes out his own share of the bad guys. Contrast that with a clear influence, “48 Hrs.,” in which the roles of comic relief and action type are clearly delineated, as well as making the opposites so starkly juxtaposed that it becomes almost farcical. Black’s “Lethal Weapon” (and subsequent films) found more common ground between his two leads and also found a lot of heart that grew out of that camaraderie. And with that, a template was born to which Black would return for at least three more films, redefining what audiences could expect from a high-caliber buddy cop movie.

But rather than seem like he’s repeating himself, or simply working in the exact same tropes as before, each of the later entries would feel new to audiences. That’s because Black changed it up, focusing on different marginalized outsiders to lead the charge against a member of an old guard that is doing some wildly illegal stuff just to make a buck. “The Last Boy Scout” has two disgraced men, one an ex-Secret Service agent and the other a washed out football player, taking on the corporate oligarchy that seeks to rig the system (through murder and threats) to make sports gambling legal. “The Long Kiss Goodnight” finds a woman and a black private eye squaring off against a shadowy government agency that is going to commit a false flag attack (and blame it on “the Muslims”). “Kiss Kiss Bang Bang” has a criminal and a gay private eye taking on a Hollywood producer looking to scam his way into even more money by killing off his daughter.

There are other repeated tropes in these films: a malevolent, second-in-command bad guy who the hero must face and is the real physical threat while the old, white leader simply schemes his way into success; it’s almost always set around Christmas-time; and at least one of the pair is burdened with the sins of the past that they can’t outrun. But these recurring themes never feel stale or like a retread, because Black imbues his characters with unique voices, his scripts are crackling with distinct dialogue and rapid-fire banter, and he makes sure that there is no classic “straight man” within the duo but instead gives each one their time to shine verbally and physically.

This unique voice finds its apex with Black’s directorial debut “Kiss Kiss Bang Bang,” in which the film itself becomes part of the deconstruction of action beats with multiple breakings of the fourth wall and playing with the language of movies. In each film, Black brings back the tropes that interest him, but he does so in a different way without losing the playfulness of working within the forms of the subgenre. That playfulness mixed with serious action (and signature stylistic tics) is absent from other films; they are either too dour (“Cradle 2 the Grave,” “The Glimmer Man”), or too silly (“Blue Streak,” “Bad Boys”), failing to strike the proper balance of action with consequences and humor naturally born from the characters’ interactions.

Even his other work outside the subgenre, like “Iron Man 3,” has those elements of the buddy cop film creeping in. When Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.) and Rhodey (Don Cheadle) infiltrate The Mandarin’s mansion, or even when they are just grabbing a bite to eat with each other, there’s that classic Black back-and-forth and the balancing of opposite abilities. Rhodey is a military man, used to precision and following orders, while Stark is the loose cannon that improvises his plans of attack, assured by his own genius for solving problems. But there is a respect and familiarity between the two that was carried over into “Avengers: Age of Ultron” and “Captain America: Civil War.” Even working in another format, Black finds a way of defying expectations and injecting the film with his signature wit, style and various tropes that preoccupy his projects and inject a sense of vitality and relatability.

Beyond “Lethal Weapon,” most of his films haven’t been smash hits commercially (save for “Iron Man 3”). However, “The Last Boy Scout,” “The Long Kiss Goodnight” and “Kiss Kiss Bang Bang” have all found their audiences, becoming cult favorites of people who enjoy whip-smart writing and the adventures of outsiders squaring off against an established and moneyed old guard. It would seem counterintuitive that a filmmaker so intent on revisiting particular themes and tropes is able to reinvent himself each time, but Black does so on the strength of his character work, presenting world-weary everymen who are simply trying to do the best they can. When looking at pale imitators like “Rush Hour,” “Collision Course” or “The Hard Way,” it becomes even more apparent that Black was not only bringing a cleverness and intelligence to his dialogue, but he was also bringing a lot of heart and care for these action heroes, which endeared them to audiences and set his films apart.

Both “Lethal Weapon” and “The Last Boy Scout” have the villains telling the protagonists that there are “no heroes” left in this world. And while the sarcastic replies and repartee suggest that these buddy cop partners should agree with that worldview, they aren’t cynical. They are doing what’s right not because it’s easy or because it’s their job, but because they are compelled to set right what has gone wrong. The cynicism found in other buddy cop movies isn’t evident in Black’s work. His heroes are interested in taking power back from those corrupt and unjust members of society’s elite who lord it over the less fortunate, but they do so not for a hero’s reward. In every case, it’s so they can be a part of a family. That’s all – it’s that simple. Riggs finds a new home and stability with Murtaugh’s wife and kids; Charly Baltimore (Geena Davis) resumes her life as an unassuming wife and mother in the countryside; Joe Hallenbeck (Bruce Willis) gets to be reunited with his daughter; and Harry Lockhart (Downey Jr.) finds a new life on a different coast with Gay Perry (Val Kilmer), creating their own makeshift family. In Black’s films, the outsiders are rewarded for their travails by finally finding where they belong and receiving some form of forgiveness for their past transgressions. There may not be heroes left in this world, but there are still those willing to fight for it.

Related Posts

Comments Off on The Buddy System: How Shane Black has continually reinvigorated and redefined the buddy cop film

Posted in: Entertainment, Movies

Tags: buddy cop films, buddy cop movies, Iron Man 3, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Lethal Weapon, Shane Black, The Last Boy Scout, The Long Kiss Goodnight