Judd Apatow’s films often cover heavy, emotionally complicated territory, but they’re ice cold at the same time. The subject matter is relatable, but the manner in which it’s treated bears little resemblance to real life. (The most egregious offender: “This Is 40.” Now let us never speak of it again.) “Trainwreck,” by comparison, is the most honest, heartfelt film Apatow has made to date, and it’s hard not to notice that it’s also the first time he directed a script that he didn’t have a hand in writing.

Some back story, for the unfamiliar: Apatow has taken heat over the years for underwriting his female roles – and yes, that criticism came largely from Katherine Heigl, who cashed some monster paychecks after receiving a massive career boost by appearing in his 2007 film “Knocked Up,” therefore people accuse her of biting the hand that fed her, and while that may be the case, she’s not wrong – and perhaps this was Apatow’s attempt to make amends, by directing a script written by a woman (Amy Schumer). The crazy thing is, Schumer’s character in many ways embodies the very traits that Heigl protested (reckless, irresponsible, unaccountable), but with the female character in the lead role, you get something that previous Apatow films never provided, and that is perspective: we get both the ‘what’ and the ‘why’ of her character’s behavior. Also, there are no shrews in this movie. Apatow’s other movies were loaded with shrews. Who likes shrews that much?

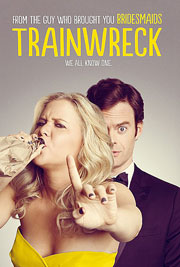

Amy Townsend (Schumer) writes for S’Nuff, a Gawker-esque magazine with roughly 75% less humanity. She also parties nonstop and sleeps around, even though she has a boyfriend (John Cena). A fellow writer pitches an article about Aaron Conners (Bill Hader), a surgeon who’s come up with a revolutionary knee procedure that will greatly reduce recovery time for athletes. S’Nuff editor Dianna (Tilda Swinton, in full Anna Wintour mode) likes the story, but assigns it to Amy, because Amy has admitted that she hates sports, and Dianna likes the idea of the paradox. Amy surprisingly finds herself fascinated with both Aaron and his work, and when she unprofessionally consummates their professional arrangement, she does unthinkable things, like actually agreeing to spend the night at his place and generally being less afraid of commitment. Amy is confused by this new change to the game plan, and she responds to it the only way she knows how: self-destruction.

The story, at its core, is a simple one. A broken girl lives a broken (but fun) life, girl sees opportunity to leave the drama behind, but a lifetime of bad habits threatens everything. Within that simple story are four relationship narratives: Amy and Aaron, Amy and her ailing father Gordon (a well-cast Colin Quinn), Amy and her resentful younger sister Kim (Brie Larson), and Amy and her boss Dianna. Each relationship could explode at any minute, but for different reasons, and in every instance, Amy is fighting a battle that the other people in her life know next to nothing about. Comedy pedigree be damned, Schumer flexes serious dramatic writing chops here.

Unfortunately, she also falls victim to the ‘underwrite the love interest’ trap. Hader’s Aaron is a perfectly nice, likable guy (his scene playing one-on-one basketball with LeBron James is a stone-cold classic), but he’s not terribly interesting, generous to a fault, and definitely not the kind of guy that Amy would be drawn to. That’s the point, of course, but there isn’t enough in his character to seal the deal, at least with a girl like Amy, for whom hanging out with superstar athletes means nothing. Schumer also stages a scene late in the movie that makes zero sense. The manner in which they set up the scene is a cheat, because it prevents us from getting the whole picture, presumably to make the subsequent, ridiculous events easier to sell. However, Amy has a good idea of what is going on, and she of all people would know not to go there.

There is also the matter of the cameo parade, which is taken to ridiculous extremes. LeBron is hilarious as himself, and there is a wonderfully pretentious movie within the movie, but the other celebrity cameos either lack the comedic timing (Amar’e Stoudemire) or necessity (the intervention) to justify inclusion. Worse, they don’t even feel like Schumer’s ideas, but rather something that Apatow thought of on the fly, and shoehorned into the film.

Fortunately, Schumer sticks the landing with a sweet and funny finale that is both self-deprecating and self-affirming, which is by no means easy to do. Indeed, Schumer’s immense likability makes even the unwatchable stuff entertaining on one level or another. “Trainwreck” is not perfect, but it’s perfect for Apatow. He needed this movie, arguably more than the movie needed him.

Related Posts

Posted in: Entertainment, Movie Reviews, Movies

Tags: Amy Schumer, Bill Hader, Brie Larson, Judd Apatow, LeBron James, Trainwreck, Trainwreck review