My first ever DOTW post back in 2011 covered the Martini. It’s nevertheless taken me until just the last few weeks to start exploring the ancestry of that most iconic of cocktails, which a lot of people assume kind of begin and ends with last week’s Martinez. Still, it’s name aside, that very good but very sweet drink has more differences than similarities with the modern oh-so-dry Martini beverage. Today, I’ve found a drink that, while still pretty sweet, really does seem to be the semi-missing link between the Martinez and the Martini.

My first ever DOTW post back in 2011 covered the Martini. It’s nevertheless taken me until just the last few weeks to start exploring the ancestry of that most iconic of cocktails, which a lot of people assume kind of begin and ends with last week’s Martinez. Still, it’s name aside, that very good but very sweet drink has more differences than similarities with the modern oh-so-dry Martini beverage. Today, I’ve found a drink that, while still pretty sweet, really does seem to be the semi-missing link between the Martinez and the Martini.

The Gin and It — “It” being short for “Italian,” as in Italian vermouth, as in sweet vermouth — is pretty much what the name implies. While some versions weirdly call for using no ice whatsoever, my version of the drink, at least, is very close to my comparatively high-vermouth starter version of a Martini, save for the species of vermouth. It’s also just about identical to my take on a Manhattan (the second DOTW), except for using gin and not whiskey.

Now, here’s the kicker. Back in 1930, Harry Craddock’s epochal The Savoy Cocktail Book, actually listed three types of Martini, one of which was called the Sweet Martini, which, like my Gin and It, calls for 2 parts gin and one part Italian vermouth. His dry version of a Martini called of one part dry vermouth and 2 parts gin. Today, of course, a dry martini typically means one with either only a hint of vermouth or even (and I don’t like this) none at all. Considering Mr. Craddock, however, it seems pretty darn likely that when the first person uttered the quip, “let’s get you out of those wet clothes and into a dry Martini” they meant a drink made with dry vermouth (perhaps Martini brand), not little or no vermouth.

Anyhow, here’s the perfect drink for anyone craving a very un-dry martini as in one that’s actually sweet….but still pretty close to an actual Martini.

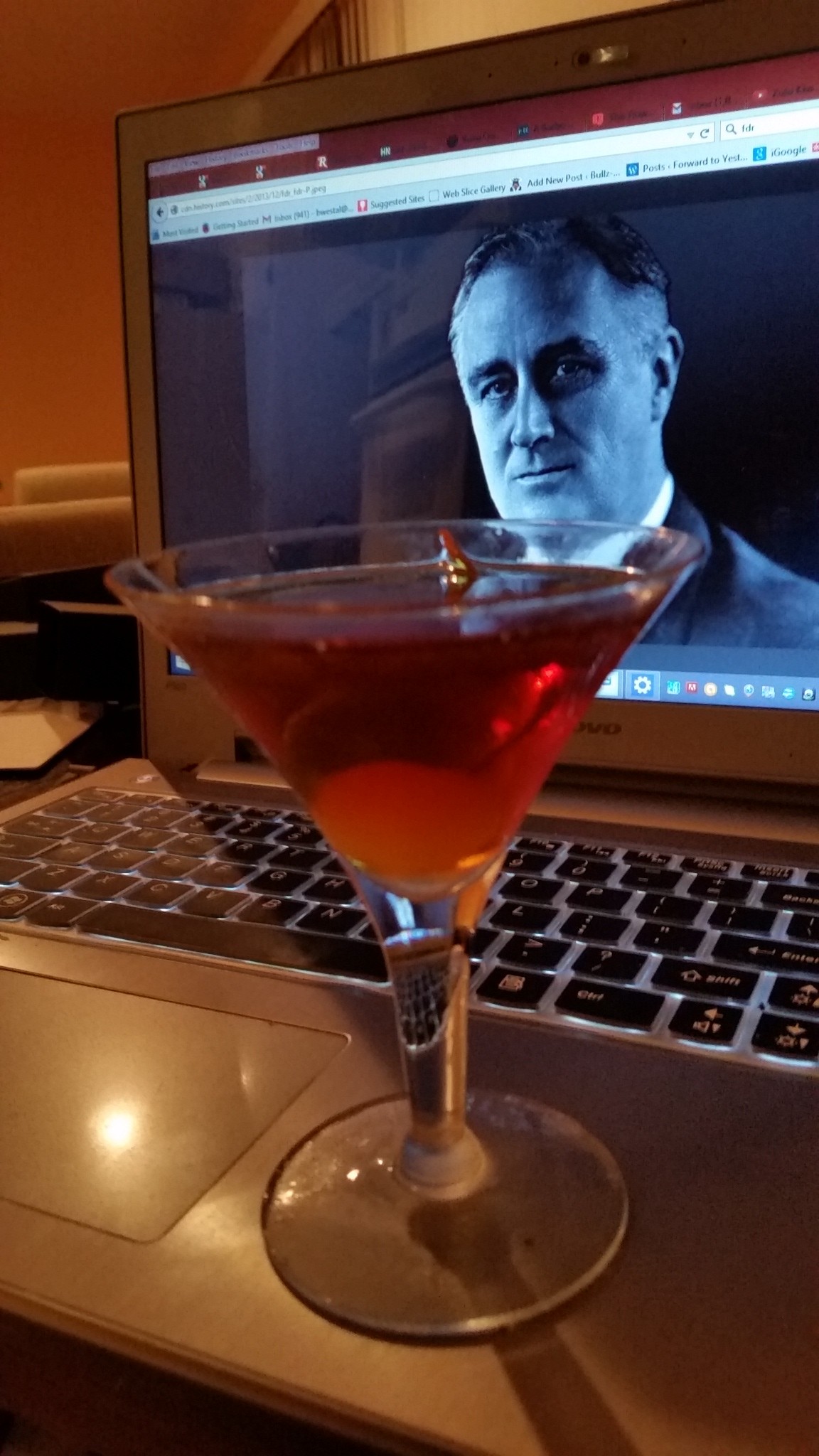

The Gin and It

2 ounces gin

1 ounce sweet vermouth

1-2 dashes aromatic bitters

1 orange twist or cocktail cherry (garnish)

Combine your liquid ingredients in a mixing glass or cocktail shaker. As if to foreshadow Ian Fleming, Harry Craddock actually instructed that ALL of his martinis should be shaken, but I prefer my martinis stirred, not shaken. (Gin seems to me to take on a slightly less pleasant flavor when shaken, don’t ask me why.) Definitely use ice. Strain into chilled cocktail glass and add the garnish of your choice, if any.

Toast vermouth, both sweet and dry. It is one of the most honorable, yet misunderstood and unfairly maligned of cocktail ingredients.

*****

While notably less complex than the Martinez, the Gin and It is also a bit drier, at least at my proportions. (Many versions call for equal parts gin and sweet vermouth.) It pretty much tastes like a Manhattan made with gin, and that’s not a bad thing . I tried this with Bombay Gin, Gordon’s Gin, Carpano Antica and, yes, Martini. While I can’t say any version of the drink rocked my world — I actually enjoyed the Martinez a great deal more — the best version was made was the higher end ingredients; I suppose that’s not a surprise. I also haven’t a clue why this drink isn’t as least as well known as, say, a Gimlet.

I will speculate, however, that the idea being promulgated in some quarters of the Internet that the platonic form of the Gin and It is made without ice might have something do with the idea. Suffice it to say, the room temperature Gin and It is not for everyone, and, this case, the everyone it’s not for includes me. It’s not that it tastes bad, it’s just that there’s a reason we dilute and chill this stuff with ice.

You’ve got relatives, I’ve got relatives. Everyone’s got relatives. The interesting thing about them is that they can have a great many of the same components that we do; at the same time, the final result can have you shaking your head and wondering how the #$@#$# it is that you share any chromosomes at all with these people.

You’ve got relatives, I’ve got relatives. Everyone’s got relatives. The interesting thing about them is that they can have a great many of the same components that we do; at the same time, the final result can have you shaking your head and wondering how the #$@#$# it is that you share any chromosomes at all with these people.

“Fin de siècle” is French for “end of the century, which means that we’ve all missed our opportunity by 15 years to have a Fin de Siècle at the most appropriate point possible, assuming we were old enough to drink in 2000. Or, if you want to look at it the other way, we’ve all got 85 years to work on preparing the perfect Fin de Siècle in time for 2100.

“Fin de siècle” is French for “end of the century, which means that we’ve all missed our opportunity by 15 years to have a Fin de Siècle at the most appropriate point possible, assuming we were old enough to drink in 2000. Or, if you want to look at it the other way, we’ve all got 85 years to work on preparing the perfect Fin de Siècle in time for 2100.

The Liberal’s history goes back to before the turn of the 20th century, which means it’s probably dangerous to make any strong connections with modern day political affiliations, especially since this drink doesn’t have any particular story to go with it. When it comes to political labels, in any case, a lot of things have changed since 1895. That’s why modern day conservative writers feel like they can argue that they are the real liberals — as in libertarian — while today’s liberals are, in fact, fascists — a political affiliation that I’m pretty sure didn’t exist when the Liberal was first being mixed. Also, I think there’s maybe kind of a big difference between Benito Mussolini and Adlai Stevenson.

The Liberal’s history goes back to before the turn of the 20th century, which means it’s probably dangerous to make any strong connections with modern day political affiliations, especially since this drink doesn’t have any particular story to go with it. When it comes to political labels, in any case, a lot of things have changed since 1895. That’s why modern day conservative writers feel like they can argue that they are the real liberals — as in libertarian — while today’s liberals are, in fact, fascists — a political affiliation that I’m pretty sure didn’t exist when the Liberal was first being mixed. Also, I think there’s maybe kind of a big difference between Benito Mussolini and Adlai Stevenson.

If Christmas is a movie directed by Frank Capra as in “It’s a Wonderful Life,” then New Year’s and New Year’s Eve is a movie directed by Billy Wilder as in “The Apartment.” One is a holiday about what’s really important: family, love, friendship, and being good to your fellow man. The other is a holiday about what’s really important: sex, drinking, and being able to look at yourself in the mirror after the sex and the drinking have run their inevitable course. I don’t think there’s any mystery why a drink named the Hanky Panky caught my eye as a possible New Year’s beverage.

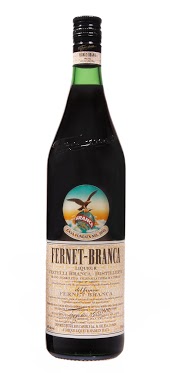

If Christmas is a movie directed by Frank Capra as in “It’s a Wonderful Life,” then New Year’s and New Year’s Eve is a movie directed by Billy Wilder as in “The Apartment.” One is a holiday about what’s really important: family, love, friendship, and being good to your fellow man. The other is a holiday about what’s really important: sex, drinking, and being able to look at yourself in the mirror after the sex and the drinking have run their inevitable course. I don’t think there’s any mystery why a drink named the Hanky Panky caught my eye as a possible New Year’s beverage. While I’m too cheap to buy the finest Cognac, I used my sturdy and very reasonably priced fallback brandy of Reynal (with offices in the Cognac region of France) which you can buy for about $12.00 at Trader Joe’s and BevMo. The Reynal and the wondrous

While I’m too cheap to buy the finest Cognac, I used my sturdy and very reasonably priced fallback brandy of Reynal (with offices in the Cognac region of France) which you can buy for about $12.00 at Trader Joe’s and BevMo. The Reynal and the wondrous