Drink of the Week: The Cognac Sazerac

There was a time when calling a drink a cognac sazerac would have been close to calling a certain sandwich a “beef hamburger.” However, New Orleans’s magnificent contribution to classic cocktails has changed over the years. Today, it is almost always prepared with rye whiskey but, as I pointed out in my prior post on this great beverage, it was originally a cognac-based drink.

There was a time when calling a drink a cognac sazerac would have been close to calling a certain sandwich a “beef hamburger.” However, New Orleans’s magnificent contribution to classic cocktails has changed over the years. Today, it is almost always prepared with rye whiskey but, as I pointed out in my prior post on this great beverage, it was originally a cognac-based drink.

The occasion for my welcoming in 2012 with a reconsideration of an old favorite was the kind and savvy decision of the Hennessy company to send me a bottle of their relatively young, but still very drinkable, Hennessy VS Cognac. I’m not a huge cognac or brandy connoisseur at this point, but I’m starting to see what all those rappers and the late Kim Il Sung saw in the stuff. In fact, I sort of accidentally mostly polished off the bottle sooner than I meant this last Christmas Hanukkah when I got overenthusiastic making Sidecars — with Cointreau, at last — for family. I also tried one of their recipes, the Hennessy citrus, which wasn’t bad but was kind of sour for my taste. I think the addition of a bit of egg white. as in this variation, might have helped.

Nevertheless, I had enough Hennessy VS left to revisit what I might actually argue is the more readily enjoyable version of this great cocktail. Harder edged drinkers may prefer the whiskey based drink, but I’m here to tell you this one may well be preferable for those with softer taste buds.

The Cognac Sazerac

2 ounces cognac

1 teaspoon superfine sugar or 1 sugar cube

1/2 ounce of water

2-3 dashes of Peychaud’s bitters

1 teaspoon Herbsaint

Lemon twist

Start by chilling a rocks glass, either by filling it with ice or leaving it in the freezer or, ideally, both. Dissolve a teaspoon of superfine sugar by stirring it in a cocktail shaker or room temperature rocks glass with unchilled water, whiskey, and bitters. (If you want to go super traditional, leave out the superfine sugar and muddle a sugar cube into the same mixture instead.) Once the sugar is dissolved, add plentiful ice. If you want to conserve water, and you should, you can use the same ice you’ve been using to chill your rocks glass.

Take your now well-chilled glass and add a teaspoonful of Herbsaint, a very sweet but strongly anise flavored liqueur. Swirl the liquid carefully, holding the glass sideways. The idea is to coat it with the Herbsaint. Then, turn the glass upside down over a sink, dumping out any remaining liquid. Now it’s time to grab your cognac and fixings filled shaker and shake it very vigorously. Strain the result into the chilled and Herbsainted glass.

Then, take your lemon twist and run it along the edge of the glass. Twist the lemon peel over the beverage to magically deliver lemon oil to the drink. Drop it in. Sip while listening to the New Orleans music of your choice.

***

A few notes about ingredients and practices. For starters, It’s actually more traditional to use absinthe but, having just purchased my first bottle of the once illegal stuff, I wasn’t wowed. Both liqueurs are heavy on the anise, but absinthe has a bitter edge that I was not too thrilled by. So far, at least, I personally prefer the kinder, gentler, and cheaper sweetness of Herbsaint in a sazerac. There is also a shaking vs. stirring debate here to some degree, but I don’t get why you’d want to stir it. Froth is your friend in a sazerac, I say.

Also, though I really did enjoy the Hennessy VS Cognac, feel free to use your favorite straight-up brandy. Most regular brandy is to cognac as champagne is to sparkling white wine. It’s basically the same, just made from grapes grown in a different part of the world.

You can follow us on Twitter and Facebook for content updates. Also, sign up for our email list for weekly updates and check us out on Google+ as well.

Posted in: Food & Drink, Lifestyle, Vices

Tags: absinthe, Angostura Bitters, cocktails, cognac, Drink of the Week, Happy Hour, Hennessy VS Cognac, Herbsaint, New Orleans, Old Fashioned, Peychaud's bitters, rye, sazerac, whiskey

Have you ever found yourself wondering exactly what a hot toddy is? I know I have. I’ve had them in bars maybe once or twice at most and occasionally messed around with heating up some whiskey and water with a little sugar or something else, but I’ve never quite had a handle on what makes a toddy a toddy. The funny part is that after working with them a bit more earnestly the last week or so, I’m still wondering what a hot toddy is.

Have you ever found yourself wondering exactly what a hot toddy is? I know I have. I’ve had them in bars maybe once or twice at most and occasionally messed around with heating up some whiskey and water with a little sugar or something else, but I’ve never quite had a handle on what makes a toddy a toddy. The funny part is that after working with them a bit more earnestly the last week or so, I’m still wondering what a hot toddy is.

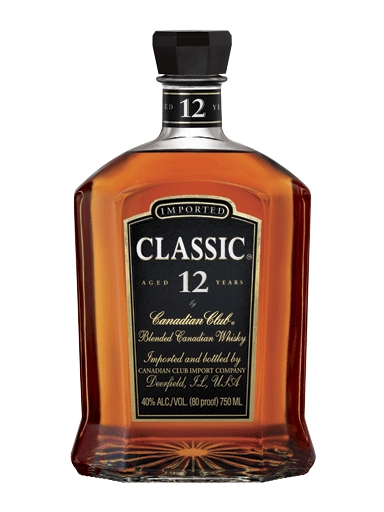

Sometimes referred to, particularly in Canada, as rye despite the fact that it’s primarily made with corn spirits, Canadian whisky, unlike now resurgent American rye whiskey, never threatened to go away. Still, while some uninformed bartenders still think rye is just the name of a type of Jewish bread, it’s the rare bar that doesn’t stock Seagram’s V.O., Canadian Club, Crown Royal and often Black Velvet. Its the even rarer connoisseur or cocktail aficionado who will admit to being excited about them, with some liquor snobs deriding Canadian as “brown vodka.” Following their lead, younger drinkers who have taken to premium brands of bourbon and Scotch, have largely ignored it. That’s not to say unassuming Canadian Whisky has no fans among the cognoscenti. We kind of love it and no less an authority than cocktail historian

Sometimes referred to, particularly in Canada, as rye despite the fact that it’s primarily made with corn spirits, Canadian whisky, unlike now resurgent American rye whiskey, never threatened to go away. Still, while some uninformed bartenders still think rye is just the name of a type of Jewish bread, it’s the rare bar that doesn’t stock Seagram’s V.O., Canadian Club, Crown Royal and often Black Velvet. Its the even rarer connoisseur or cocktail aficionado who will admit to being excited about them, with some liquor snobs deriding Canadian as “brown vodka.” Following their lead, younger drinkers who have taken to premium brands of bourbon and Scotch, have largely ignored it. That’s not to say unassuming Canadian Whisky has no fans among the cognoscenti. We kind of love it and no less an authority than cocktail historian  It might seem a bit odd, but it was current MSNBC political goddess and past Air America star Rachel Maddow whose radio “cocktail moments” largely propelled your loyal scribe’s fledgling interest in

It might seem a bit odd, but it was current MSNBC political goddess and past Air America star Rachel Maddow whose radio “cocktail moments” largely propelled your loyal scribe’s fledgling interest in